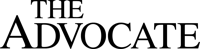

A state marker commemorates the Morrisonville community near Plaquemine.

She's known as the "Cemetery Lady" in West Baton Rouge and Iberville parishes, but if it weren't for Debbie Doiron Martin, some people would never have existed.

Or that's how it would seem if she didn't trudge through vine-covered forests and petrochemical plant grounds to record the names and dates on forgotten headstones.

Yes, she's lobbied for and gained access to the grounds of a chemical plant to do her work, specifically Dow Chemical Co.'s Plaquemine Division. That's where former residents of the Morrisonville community are buried in two cemeteries.

The gravesite of Willie Reason in Nazarene Baptist Church Cemetery on the grounds of Dow Chemical in Plaquemine. The cemetery is the burial place for the descendants of the freed slaves of Australia Plantation, who formed the Morrisonville community in Iberville Parish.

Some of those residents were probably family members of Andrea Snearl's grandmother, who told stories about growing up on Australia.

"She was born in 1917, and it wasn't until I was older that I realized that she was talking about Australia Plantation, located in either Iberville or West Baton Rouge Parish," the Brusly resident said. "Did such a place exist?"

The short answer to Snearl's question is yes, Australia Plantation did exist on a peninsula in the Mississippi River known as both Australia Point and Sardine Point on the opposite side of the river from Baton Rouge. The plantation's freed slaves founded their own community in the 1870s in the nearby vicinity.

They called the community Morrisonville in honor of the Rev. Robert Morrison, who founded the community's Nazarene Baptist Church in 1889.

The gravesite of George Cole in Nazarene Baptist Church Cemetery on the grounds of Dow Chemical in Plaquemine. The cemetery is the burial place for the descendants of the freed slaves of Australia Plantation, who formed the Morrisonville community in Iberville Parish.

"There's still a little jetty where Australia Point used to be," Martin said. "When it's super dry, you can still go out there and see the old levee."

According to The Advocate's 1991 article, "The Death of a Town: A Chemical Plant Closes In," the "tightly knit community, it had remained largely intact, with the same Baptist church and the same family bloodlines, for more than a century."

Well, actually, there were two churches that served the community, but the article continues: "It survived spring floods when it was outside the levee and it survived a government-ordered relocation a few hundred yards away to higher ground inside the levee in 1932."

An iron cross is one of the oldest grave markers in Nazarene Baptist Church Cemetery on the grounds of Dow Chemical in Plaquemine. The cemetery is the burial place for the descendants of the freed slaves of Australia Plantation, who formed the Morrisonville community in Iberville Parish.

But in 1991, Dow expanded its operation, spending some $10 million in a voluntary buyout of the community's estimated 250 residents.

"Now you have two communities from the old Morrisonville community," Martin said. "Some of them settled in Plaquemine."

Others relocated in the Morrisonville Estates community in Iberville Parish and the Morrisonville Acres community in West Baton Rouge Parish.

"That was part of the buyout," Martin said.

The gravesite of L. Johnson in Nazarene Baptist Church Cemetery on the grounds of Dow Chemical in Plaquemine. The cemetery is the burial place for the descendants of the freed slaves of Australia Plantation, who formed the Morrisonville community in Iberville Parish.

Now all that remains on its original grounds are the community's two cemeteries, which the chemical plant maintains. One cemetery serves the congregation of the Nazarene Baptist Church, which was relocated to La. 1. The other serves the lost Mount Olive Baptist Church.

"I think St. Mary Baptist Church in Plaquemine is connected to the Mount Olive cemetery," Martin said. "I'm just now starting research on that one, but the cemeteries are still active, and they're open to the community. They just need a sheriff's deputy to escort them back there."

Martin knows this because she's not only talked to the former residents but has had to secure her own deputy escort to visit the cemeteries. Again, she's known as the Cemetery Lady, the local genealogist who documents lineages of lost communities, most of which are Black communities.

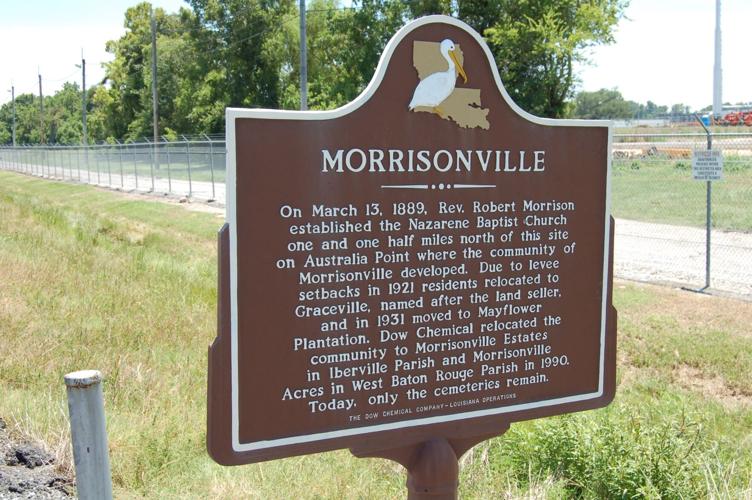

The gravesite with an illegible headstone in Nazarene Baptist Church Cemetery on the grounds of Dow Chemical in Plaquemine. The cemetery is the burial place for the descendants of the freed slaves of Australia Plantation, who formed the Morrisonville community in Iberville Parish.

"Unfortunately, for a lot of these cemeteries, because of when they were formed, records weren't required at the time," Martin said. "You have to consider that these cemeteries were in existence in the late 1800s, and Louisiana didn't require death certificates until 1914."

So, from the 1800s until 1914, the headstones are the only proof that many of those buried there existed.

"There will be no record of the slave burials unless the plantation owners made their slaves become Catholic," Martin said. "Well, then from 1914 till the 1960s, African Americans were still considered lower class people, and therefore, you look at a death certificate and it might say, they're buried in Addis. Well, there are seven cemeteries. How do you know which one? So, a lot of information has been lost."

The gravesite of Louis Williams Jr. is one of the most recent in Nazarene Baptist Church Cemetery on the grounds of Dow Chemical in Plaquemine. The cemetery is the burial place for the descendants of the freed slaves of Australia Plantation, who formed the Morrisonville community in Iberville Parish.

This is something Martin had to explain to Dow when making her case to document the cemeteries on the company's land. When doing her work, Martin must photograph the cemeteries' headstones.

Though there is no blanket federal law prohibiting the photographing of petrochemical plants, companies can restrict photography on their private property. Dow does not allow photography in or of its plant, but Martin's mission was to photograph only the headstones.

The Catch-22 was that the headstones are within the plant's perimeter.

The gravesite of Miss Kitty Thompson in Nazarene Baptist Church Cemetery on the grounds of Dow Chemical in Plaquemine. The cemetery is the burial place for the descendants of the freed slaves of Australia Plantation, who formed the Morrisonville community in Iberville Parish.

"The first attempt I made, they were not going to allow me in there because you can't photograph inside," Martin said. "I talked to someone, went further up and up and tried to explain, in some cases, that headstone is the only written document that a person even existed. And I could prove it to them, that this is what we need to document them before they're gone."

The company finally granted access to Martin with an escort in and out of the plant. She was able to photograph the headstones, though a few possessed little or no information, which wasn't unusual for the times.

This is a volunteer effort on Martin's part. She has a full-time job, but she knows if she doesn't document the cemeteries at Dow, along with others in the area, these family and community histories eventually could be lost to time.

The gravesite with an illegible headstone in Nazarene Baptist Church Cemetery on the grounds of Dow Chemical in Plaquemine. The cemetery is the burial place for the descendants of the freed slaves of Australia Plantation, who formed the Morrisonville community in Iberville Parish.

And that could include the family of Snearl's grandmother, who was born at Australia Point.

On Dec. 12, 2004, Dow erected a state historical marker telling the Morrisonville community story near its entrance along La. 988.